Jonjo Shelvey, Addiction, and the Lonely Geography of Professional Football

When discussions about footballers and addiction surface, they are often framed as individual failure stories. A player couldn’t cope. A player made poor choices. A player lacked discipline. What gets lost in that narrative is the environment professional football creates, and sustains around young men long before the spotlight ever finds them.

Jonjo Shelvey’s openness about addiction invites a more honest and uncomfortable conversation. Not about one footballer, but about a system that routinely places players in isolation, strips away independent identity, and then expresses surprise when coping strategies turn destructive.

Professional football is uniquely nomadic. Players spend vast portions of their lives in hotels, up and down the country, across Europe, and increasingly across the world. These are not holidays. They are transient holding spaces: anonymous rooms, unfamiliar cities, disrupted sleep, separation from family, and long hours of waiting. Waiting to train. Waiting to play. Waiting to be selected. Waiting to be valued.

This is their job, and part of the reason behind the high rewards they receive. I do not speak on this to remove this scenario, as this is something that cannot be done. However, players can be prepped and developed to withstand the negative outcomes that can occur.

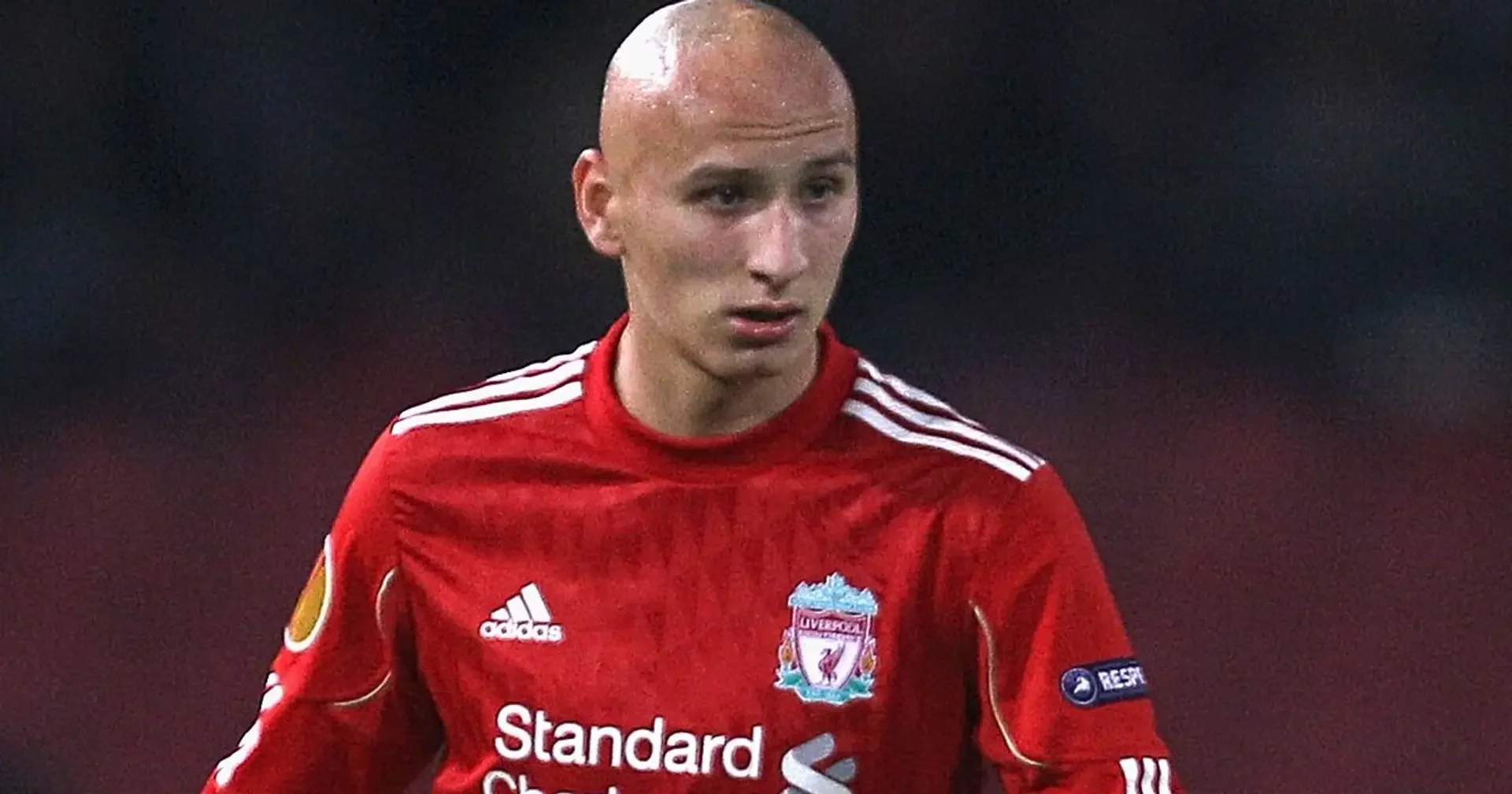

Jonjo Shelvey during his playing days at Charlton Athletic FC

Hotels, Isolation, and the Psychology of Disconnection

Hotels remove friction from life, no cooking, no cleaning, no routine. But they also remove anchors. There is no sense of ownership, no community, no continuity. For players who entered academies as children, this can echo a deeper pattern: life organised entirely by others.

In youth academies, identity becomes narrow very early. You are not a young person who plays football; you are a footballer. Education (level of study), creativity, relationships, and autonomy are often treated as secondary, or worse, distractions. By the time a player reaches the professional game, many have never been supported to develop an identity outside performance.

When that identity is threatened, through injury, form, deselection, or public criticism, the psychological impact is profound. Addiction does not emerge in a vacuum. It emerges where there is pain, boredom, loneliness, and a lack of meaning beyond results.

Hotel rooms become places where no one is watching, no one is asking questions, and no one is checking in, not emotionally, anyway. Substances, gambling, compulsive behaviours, and escapism can quietly take root, long before anyone notices.

Jonjo Shelvey during his playing days at Liverpool FC

The Myth of “Support” in Elite Football

Most clubs will point to player welfare officers, psychologists, or wellbeing programmes. On paper, support exists. In practice, much of it is reactive, compliance-driven, or structurally conflicted.

Players know, often instinctively, that honesty can carry risk. Selection decisions, contract negotiations, and public narratives are all tied to perceived robustness. Admitting vulnerability inside the same institution that controls your career is not psychologically safe for many players.

This is where football needs to evolve.

What players require is not just in-house welfare, but engagement services, professionals who are not tied to selection, contracts, or performance metrics. People whose sole role is to support the human being, not the asset. Engagement services can be anything from organising “games nights” to support with signing up to further education.

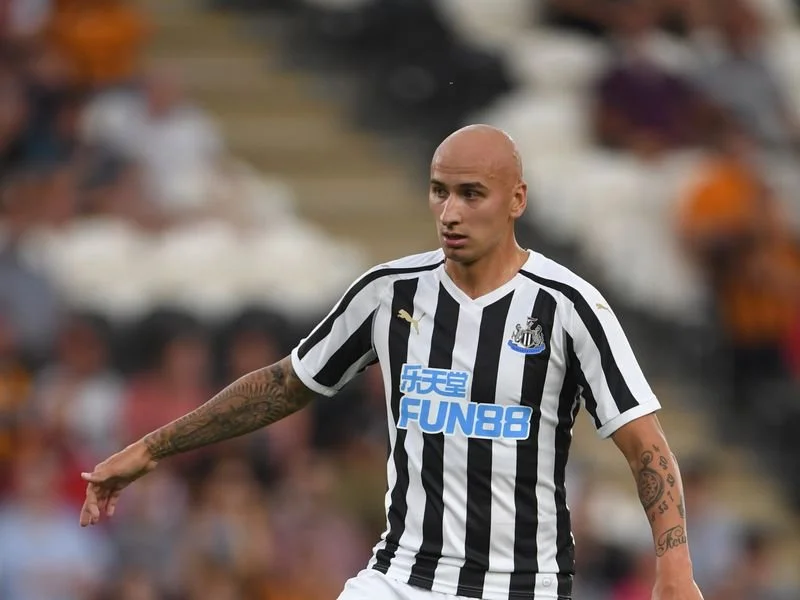

Jonjo Shelvey during his playing days at Newcastle United FC

Identity Development Should Start in the Academy

Rather than damage control, identity development must begin at academy level.

Young players need structured support to explore who they are beyond football:

Education that is meaningful

Exposure to creative, vocational, and leadership pathways

Psychological work that builds self-concept, values, and autonomy

Normalisation of emotional literacy, beyond resilience rhetoric

This is not about diluting ambition. It is about protecting it. Players with a stable sense of self cope better with setbacks, transitions, and endings, whether those endings come at 22 or 35.

Without this foundation, addiction risk is not an anomaly; it is a foreseeable outcome.

Jonjo Shelvey during his playing days at Nottingham Forest FC

A Systemic Responsibility, Not an Individual One

Jonjo Shelvey during his playing days for England

Jonjo Shelvey’s story should not be consumed as gossip or cautionary tale. It should be treated as data. Evidence that the current model, despite its wealth, science, and performance sophistication, still neglects the inner lives of players.

Football has become excellent at developing bodies and tactics. It remains inconsistent at developing people.

Clubs invest millions in physical conditioning, analytics, and recovery. Yet many still see independent psychological engagement as optional, or something to introduce only after a crisis.

The question football must ask itself is simple:

Are we developing footballers, or whole humans who happen to play football?

Until that answer changes, hotel rooms will continue to be quiet risk zones. Addiction stories will continue to surface. And players will continue to carry struggles alone in a system that prides itself on teamwork.

Real player welfare is not reactive. It is relational, independent, and identity-focused. And it should be as non-negotiable as a medical assessment or a fitness test.

Because no one should have to lose themselves to succeed in the game they love.